The Rāmāyaṇa, (रामायन or रामायण) is derived from राम and आयन आयेन, आयिन (literally meaning comes, joins, in Avadhī language), thus Rāmāyaṇa literally meaning in which Rāma comes or joins. It is therefore important to understand and use a language for the source of Rāma’s story that properly reflects the context, culture, and character of the characters involved.

In the Matsya Purāṇa, there is a reference, which suggests Vaivasvata Manu, the primordial origin of humanity in the current period, being of the Dravidian origin, who moved to Ayodhyā during the epochal deluge (Singh, 2021: “A New Narrative of Ayodhya as the Nanihal of Humanity,” Vedic Waves blog, August 6, 2021).

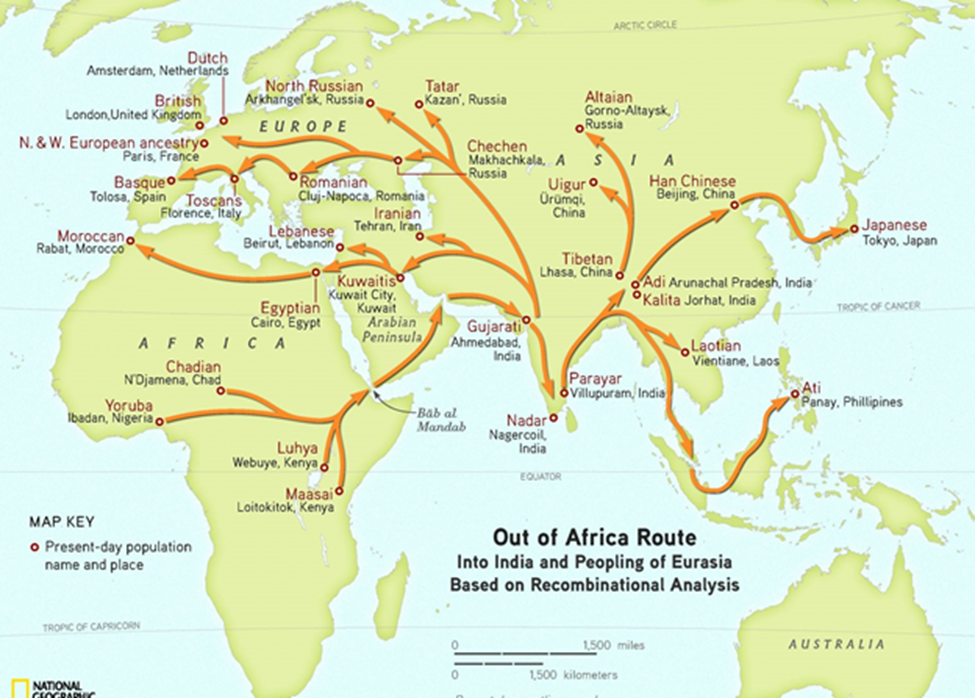

Interestingly, in a genetic study by National Geographic Society (See, Singh, 2021, above), it has been proven that human population initially migrated from Africa to the Indian Subcontinent and then from here to everywhere else, making India as the main source of human migration some 60,000 years ago. This may provide further cultural and linguistic connections with Ayodhyā and Avadhī to rest of the world. Avadhī, thus, becomes a prime source of many languages. Exploring links between literature of Avadhī and other languages could provide a whole new gamut of research. For example,

Avadhī English Sanskrit

Nani nanny matamahi

Nika nice sobhanam

Bara burn prajwalita

Tohara your tava

Niyare near nikata

Avadhī language, therefore, justifiably brings out passion in India that it is a torch-bearer of a civilization, which has sung the deeds of Rāma, Raghu, and Hariscandra! One could easily surmise why Sant Tulasidāsa decided to write Rāmacharitamānasa in Avadhī, although his mother-tongue was Brajabhāṣa. He came from Soron, Kasganj district in Uttar Pradesh, and he was a scholar in the most sophisticated known on Earth, that is Sanskrit, but decided to compile his thoughts about the story of Rāmāyaṇa in Avadhī.

With his experience (he was already 75 years old by then), he could have easily understood that Avadhī is the best language to communicate the original culture of Ayodhyā, both symbolically and linguistically. We have often seen how Bollywood movies also script this language effectively for the portrayal of rustic characters like milkman (dudhwālā), gardener (mālī), or cook (rasoiyā), who more often than not usually come to Mumbai from the Avadh region of Uttar Pradesh. It just communicates better the culture, values, and behavior of the people portrayed in those roles.

Avadhī is spoken by over 65 million people throughout the world, including the places like Fiji, Mauritius, Caribbean countries and also in some pockets of American and European continents. Its linguistic overlap and affinity with Bhojpuri, Angika, Chhatisgarhi, Bundelkhandi, Bengali, Marathi, etc. make the ambit of this language even more widespread.

A culture is quite heavily carried through food, dress, and language with native or regional connotations. This was also true in the ancient times, when long distance travels were limited. This made the source of food, dresses, and even language of communication very local. Over the years, human ingenuity produced variations in culinary preferences, sartorial sense, and exchange of ideas. But with passage of time, sometimes quaint expressions, monologues, or dialogues have created problems in their interpretation. Tulsi Rāmāyaṇa, ‘the Ramcharitmānas’, thus becomes the most authentic source of information from the Rāma story.

With that prologue, let’s explore Rāma and his values for the contemporary time. Although temple is not part of the deep Indian traditions, as one can hardly find any reference to any large structures of temple either during Rāmāyaṇa period or Māhābhārata period, yet India’s temple structures from north to south, and east to west, reflect the many marvels of architectural designs and construction feats.

Temples, likely borrowed from the Buddhist structures and Church culture, represent symbolic consideration and communication, and provide a target of dedication and devotion, something that was primarily taken care by the Gurukula, that provided direct interactions with Gurū, the source of knowledge with full clarifications made available through the questions and clarifications. With these premises of Rāmāyaṇa and Rām Mandir, let’s explore a few fundamental values of Rāma in Rāmāyaṇa.

There is a common belief that Rām, the incarnation of Bhagavān Viṣṇu, has been an ideal son, an ideal brother, an ideal husband, and an ideal father.

प्रात काल उठिके रघुनाथा, मातु पिता गुरु नावहि माथा।

Prātkāl uthike raghunāthā, mātu pita guru nāwahi māthā.

This just goes a long way to show how devoted he was to his parents, both the father and his mothers. Similarly, according to Ramcharitmānas, he cries at the time Lakṣaman gets hit by Meghnāth’s śakti and becomes unconscious.

जौ मैं जनत्यों बन्धु बिछोहू, पिता बचन मनत्यों नहि वो हू।

jau main janatyon bandhu bichhohū, pitā bachan manatyon nahin wohū.

Had he known this potential separation from his brother, he would have even ignored his father’s words that he had given to exile which resulted in potentially losing his brother.

जब जब रामु अवध सुधि करहीं, तब तब बारि बिलोचन भरहीं ।

सुमिरि मातु पितु परिजन भाई, भरत सनेहु सीलु सेवकाई।

Jaba jaba ramu avadha sudhi karahi, taba taba bāri bilocana bharahi.

Sumiri mātu pitu parijana bhāi, bharata sanehu silu sevakā. 140.2

Every time Rāma thought of Ayodhyā, his eyes filled with tears. The gracious Lord became sad when He recalled his father and mother, his family and brothers and particularly the affection, amiability and devotion of Bharata.

Similarly, Bharata was an equally devoted brother to Rāma.

भरत सरिसा को राम सनेही, जगु जप राम रामु जप जेही। 217.4

bharata sarisā ko Rāma sanehi, jagu japa Rāma ramu japa jehi. 217.4.

Who is there who loves Rāma as Bharata loves. World repeats Rāma’s name where Rāma repeats name of Bharata.

In the same vein of family love, Rāma loved his wife, Sītā, to no limit, by not only taking vrat for one wife when it was a common practice for royals to have multiple wives.

According to Shrimad Bhāgavat (SB), SB 9.10.54

eka-patnī-vrata-dharo rājarṣi-caritaḥ śuciḥ

sva-dharmaṁ gṛha-medhīyaṁ śikṣayan svayam ācarat

Bhagvān Rāmacandra took a vow to accept only one wife and have no connection with any other women. He was a saintly king, and everything in his character was good, untinged by qualities like anger. He taught good behavior for everyone, especially for householders, in terms of varṇāś Rāma-dharma. Thus, He taught the general public by his personal activities.

Additionally, he waged a very uphill and extremely dangerous war with a very powerful enemy, ordinarily a sure death step at that time.

There were apparently no instances of a close relationship with his own children, Lav and Kush, as they were born, away in the forest. Based on the scenes from the Rāmāyaṇa serial by Rāmanand Sagar, he was a loving father to his children and the children of his brothers.

These are the ideal behaviors the contemporary society could understand, adopt, and follow in their lives. However, looking from the scientific culture we have developed in the modern time, and a more holistic approach to knowledge, the inductive or the Āgama pedagogy of observations, hypotheses, principles and theories, one must consider the opposites or the behavior under contrary conditions to obtain.

धीरज धर्म मित्र अरु नारी। आपद काल परिखिअहिं चारी।।

Dhīraj dharam mitra aru nārī Āpad kāl parakhiye chārī! (Arandya Kand Ramcharitmanas)

In the time of crisis are the (deep waters) of patience, dharam (principles), friends and women (wife/partner) tested! This means under the most difficult situations, one’s patience, principles, and time test friends who have stood by, and the trusted life partner, are all tested by their behavior of standing by with their integral values.

What those strenuous conditions may have been in Rāma’s life need to elaborated and his approaches need to be understood, and his conducts need to be understood for adoption to bring Rāmrājya on this Earth.

Prof. Bal Ram Singh, President, Institute of Advanced Sciences, Dartmouth, USA